Altered Gut Microbiota Could Be Therapeutic Target in Rett Syndrome, Study Suggests

The altered gut bacteria found in girls with Rett syndrome influence their gastrointestinal symptoms and disease severity, making the gut microbiota a potential therapeutic target with probiotic supplementation or diet plans, a review study reports.

The review, “Rett Syndrome and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders Share Common Changes in Gut Microbial Community: A Descriptive Review,” was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

The variable severity of Rett syndrome cannot be fully explained by the distinct genetic profiles of patients. As such, scientists have been increasingly looking at the gut microbiota — the microbes (bacteria, fungi, and viruses) living in the digestive tract — as a key modulator of clinical symptoms.

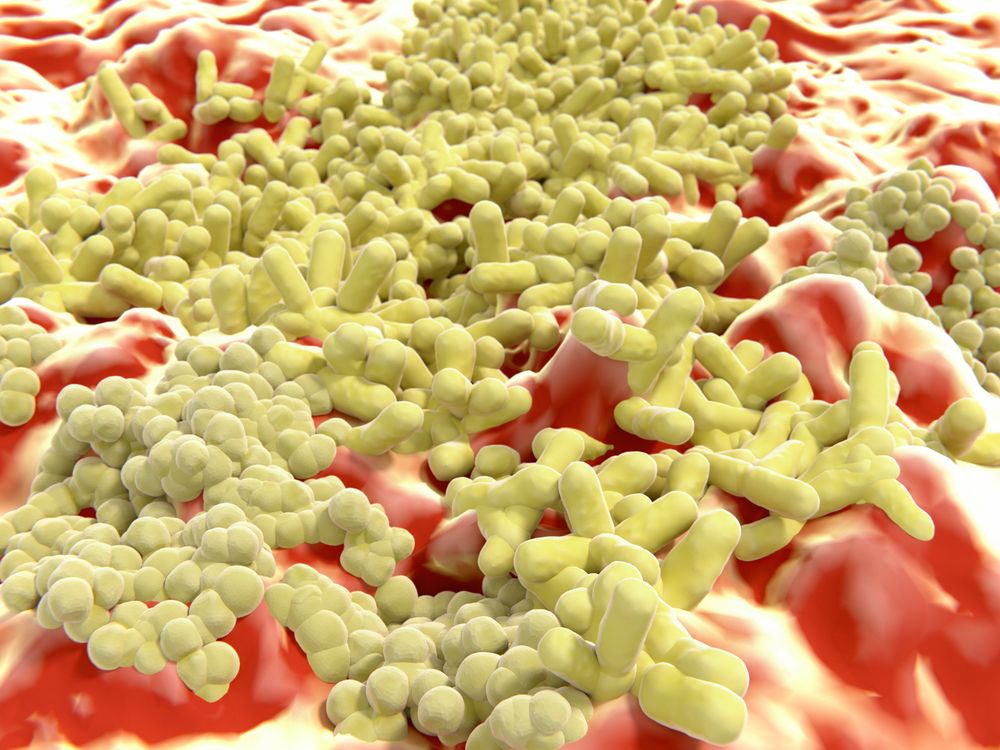

The composition of the gut microbiota is unique to each individual. More than 1,000 different bacterial species can be found, but only 150 to 170 predominate in any one person. Increasing evidence shows that diet, age, stress, and diseases may affect the abundance and diversity of gut microorganisms, which in turn can have an impact on well-being, immune responses, and neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and Down syndrome.

Although research of the microbiome in Rett syndrome is still in its early stages, investigators have uncovered a shift in the composition of gut bacteria in children with ASD, which shares similar neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms with Rett syndrome.

ASD patients appear to have a greater number of bacterial species that promote inflammation, and that can disrupt gut permeability and its barrier function.

The gut and brain communicate via immune responses, microbial-derived products, and nerves — the so-called microbiota-gut-brain axis. Specifically, substances produced by gut microbes during metabolism, particularly short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), could play a key role in the link between the gut and several other organs, including the brain.

Two studies have investigated the gut microbiota in Rett syndrome patients, the first in 50 girls (mean age of 12) and the second in eight girls (mean age of 23). No patient used antibiotics or probiotics (which can alter the gut microbiome) within three months of the start of the studies.

Results showed that, overall, girls with Rett syndrome had a less diverse community of bacteria in the gut, with higher levels of bacteria of the genus Clostridium spp., Sutterella spp., and Escherichia spp. compared with the controls. The researchers found that two groups of bacteria were more abundant in patients than in the controls — Bifidobacterium in the first study and Bacteroides in the second study.

Loss of microbial diversity is considered a hallmark of dysbiosis, an imbalance in the microbiota that can make the gut more vulnerable to disease-causing microbes and inflammation.

“Thus, the gut microbial ecosystem of [Rett syndrome] girls can be considered intrinsically more susceptible to disease status,” the researchers wrote.

The studies also found higher levels of specific SCFAs in the feces of the girls with Rett syndrome than in the controls. In the first study, the researchers suggested that this increase may explain why many of the patients experience gastrointestinal problems, most commonly constipation. The affected girls also had mild intestinal inflammation.

In the second study, the microbial diversity observed in Rett patients was lower in those with more severe disease.

Overall, the presence of dysbiosis in people with neurodevelopmental diseases, such as ASD and Rett syndrome, supports the development of innovative therapeutic strategies through microbiome-based treatment, the investigators wrote.

However, no clinical trials on probiotic supplementation in Rett syndrome patients have been conducted to date, and a standardized probiotic regimen is still lacking, they added.

“In addition to probiotic intervention, a careful diet survey on large cohorts of [Rett] patients would allow the development of diet recommendations that might mitigate microbiome alterations,” the team wrote.