Electrical Responses in Brain to Stimuli May Be Marker of Rett Severity

Written by |

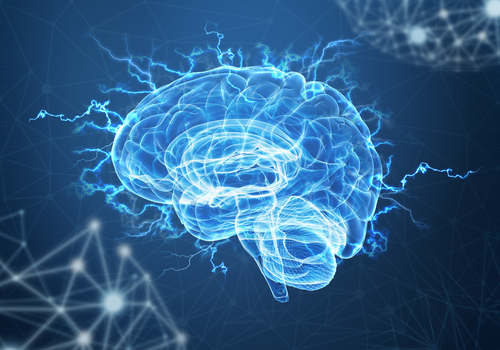

People with Rett syndrome have significantly weaker electrical responses in the brain to visual and auditory stimuli than do their healthy peers, according to an analysis of patients in a natural history study in the U.S.

The strength of these responses was also associated with both age and disease severity.

These findings suggest that brain electrical signals in response to stimuli, known as evoked potentials (EPs), might be a non-invasive biomarker of brain function and of disease severity in Rett patients. But more research is needed to confirm their value, and whether they may be used to monitor treatment response in future clinical trials, the researchers said.

The study, “Multisite Study of Evoked Potentials in Rett Syndrome,” was published in the journal Annals of Neurology and conducted by a team of researchers in the U.S.

Rett syndrome is characterized by developmental and intellectual disabilities. It is mostly caused by mutations in MECP2, a gene involved in maintaining synapses — the junctions between two nerve cells that allow them to communicate.

No disease-modifying therapy is currently approved for Rett, but several candidates are being evaluated in preclinical and clinical trials.

“With continued progress in developing targeted treatments for RTT [Rett syndrome], identifying and validating sensitive biomarkers to objectively test the effectiveness of treatments is paramount,” the researchers wrote.

Previous studies have suggested that EPs may serve as a potential biomarker of Rett syndrome, but most involved a small number of patients, and so lack sufficient power to determine their biomarker value.

EPs are electrical signals produced by the brain in response to an external stimulus, such as an image or a sound, and detected through a non-invasive test called an electroencephalogram.

Scientists set out to evaluate the potential utility of EPs as a biomarker of brain function in Rett patients as part of the Natural History Study of Rett syndrome and Related Disorders (NCT02738281), which is still enrolling across the U.S.

From an initial group of 68 females and two males with Rett syndrome, ages 2 to 37, visual EPs from 41 of them (mean age, 8.9) and auditory EPs from 47 patients (mean age, 10.7) were included in the final analysis.

A second EP measure about a year later was available for 17 patients in the visual EPs group, and for 21 in the auditory EPs group. Disease severity was assessed with two clinician-reported measures: the Clinical Severity Score and the Motor-Behavioral Assessment.

Visual and auditory EPs from 24 other individuals (16 females and eight males), with a median age of 11 (range, 2 to 25) and no history of developmental delay or neurologic, neuropsychiatric, or genetic conditions, were used as controls.

Results showed that Rett patients had significantly weaker visual and auditory EPs compared with control individuals (all defined as typically developing).

In addition, the strength of both visual and auditory EPs was significantly associated with patients’ disease severity and age, with greater severity and older age predicting weaker responses (lower amplitude).

No link between age and EP strength was found in the control group.

Weaker brain electrical responses with increasing age may represent “a generalized decline in neurologic function with age,” the researchers wrote, adding that the severity of Rett-related symptoms also “tends to increase with age.”

As such, EPs decline “may reflect a progressive aspect of the disease process in addition to correlating with interindividual differences in disease severity,” they added.

One-year analyses confirmed the observed association between EP strength and clinical severity, particularly for responses to auditory stimuli — which may be due to the relatively larger number of patients in this analysis, the researchers said.

These analyses also showed evidence of consistency in other aspects of EPs across time in many Rett patients, which is key for EPs to be considered as a biomarker.

These findings “indicate the promise of [EPs] as an objective measure of disease severity in individuals with RTT,” the team wrote.

“Our multisite approach demonstrates potential research and clinical applications to provide unbiased assessment of disease staging, prognosis, and response to therapy,” the researchers added.

They emphasized that future studies are needed to establish the criteria for which EPs are most reproducible in Rett patients, further characterize how these responses change over time, assess whether they are responsive to treatment, and determine which EP components are most suitable as a biomarker.