Changes in Gut Microbiota Associated With Disease Severity

Written by |

The richness and diversity of the gut’s microbial community, or microbiota, are reduced significantly after puberty and associated with greater disease severity in girls and young women with Rett syndrome, a study shows.

These findings add to the growing body of evidence linking Rett syndrome and altered gut microbiota.

While this study failed to find significant causal associations between changes in gut microbiota and gastrointestinal symptoms in these patients, the results may help to better understand the reasons behind such symptoms, the researchers noted.

The study, “Assessment of the gut bacterial microbiome and metabolome of girls and women with Rett Syndrome,” was published in the journal PLOS One.

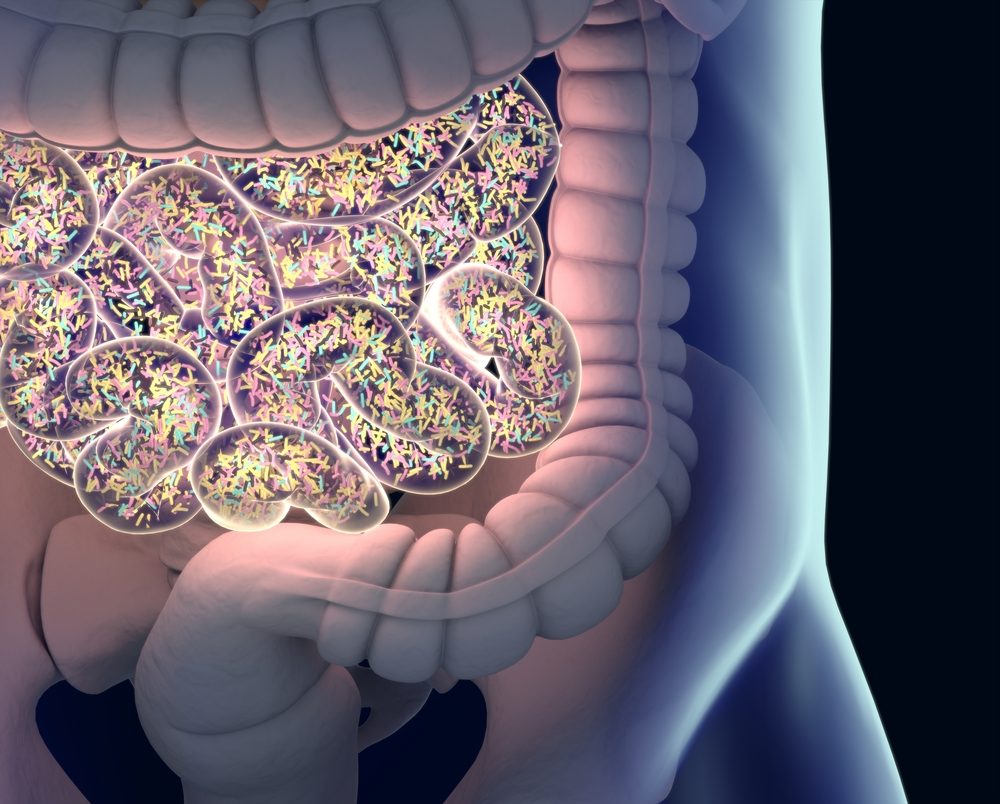

Gut microbiota comprises the vast community of friendly bacteria, fungi, and viruses that colonize the gastrointestinal tract. This community helps to maintain a balanced gut function, protect against disease-causing organisms, and influence a person’s immune system.

A well-balanced gut microbiota depends on several factors such as diet, age, antibiotic therapy, and certain diseases. A gut microbiota imbalance (dysbiosis) has been shown to trigger or worsen a number of health conditions, ranging from gastrointestinal diseases to neurodevelopmental disorders.

“More than 90% of girls with RTT [Rett syndrome] develop gastrointestinal problems that affect their health and quality of life and pose a substantial medical challenge for their caregivers,” the researchers wrote.

While an altered gut microbiota may contribute to the gastrointestinal symptoms of Rett patients, such association remains to be proven.

To date, evidence supporting this causal association comes only from two previous Italian studies in a total of 58 girls and young women with Rett syndrome, which found gut microbiota dysbiosis and altered levels of its metabolites compared with healthy individuals. Gut microbiota metabolites are the intermediate or end products of its metabolism.

To shed more light on this matter, researchers in Texas now analyzed the gut microbiota and metabolites of 44 girls and young women with Rett syndrome and 21 age-matched unaffected females without gastrointestinal disorders. They also assessed whether gut alterations were associated with gastrointestinal symptoms in Rett patients.

None of the participants, with ages ranging from 5 to 36 years, received antibiotics during the six months prior to stool sample collection. Demographic, clinical, and diet information also was collected. Rett severity was assessed with a clinical severity score.

About half of Rett patients consumed a combination of table food and commercial formulas, while about one-fourth each consumed table food or formula alone. Used formulas included whole cow milk protein source (used by 58%), a protein hydrolysate source (19%), an amino acid source (8%), a soy protein source (3%), and an alternative plant, nut, and/or meat-based source (11%).

Results showed that among girls and young women with Rett syndrome, the richness and diversity of their gut microbiota were reduced significantly after puberty and in those with severe disease, relative to those with mild or moderate disease.

This suggests an association between gut microbiota dysbiosis and Rett’s severity, consistent with findings from one of the previous Italian studies.

In addition, gut microbiota was found to be influenced by patients’ diet. Gut microbiota’s richness and diversity was lower in those receiving formula as their sole dietary source, while its composition was significantly different between patients consuming less, or more, than 4.1 grams of dietary fiber per day.

Given that diets rich in fiber have been associated with increased presence of beneficial gut microbes, collectively these findings suggest “a potential benefit of table foods, particularly a vegetable-rich, fiber-rich diet,” the researchers wrote.

No differences in gut microbiota composition were found among Rett patients based on the presence or absence of symptoms, including anxiety, hyperventilation, abdominal distention, or changes in stool frequency and consistency.

This means that a causal association between gut microbiota dysbiosis and gastrointestinal dysfunction in Rett patients cannot yet be inferred.

Moreover, and contrary to the Italian studies, the researchers found no significant differences in gut microbiota between females with and without Rett syndrome. However, the levels of three protein end products of gut bacteria metabolism — GABA, tyrosine, and glutamate — were significantly lower or tended to be reduced in Rett patients.

While the reason for these study discrepancies are not well-understood, they suggest “that increased sampling from a broad, diverse population will be necessary to appreciate fully the dysbiosis of the gut microbiome between RTT and unaffected individuals,” the team wrote.

Researchers also noted that previous studies suggested that analyzing gut tissue samples, rather than stool samples, provides a more accurate picture of microbiota alterations. As such, future studies using tissue samples are needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms of gastrointestinal problems in Rett syndrome.

Moreover, such studies “may reveal targets for manipulation of the gut microbiome for prevention or management of the gastrointestinal complications of this disorder,” the team concluded.