Music Therapy Seen to Make Mice in Rett Model More Sociable

Written by |

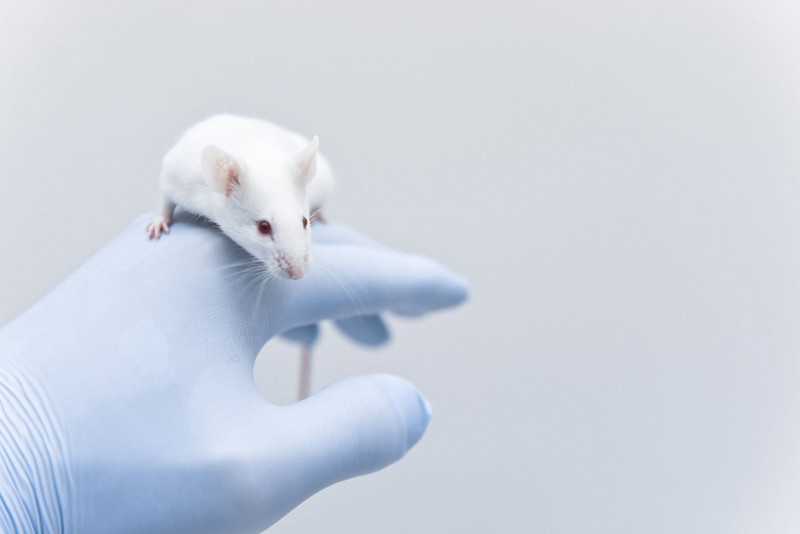

unoL/Shutterstock

A music-based intervention helped to normalize certain social behaviors in a mouse model of Rett syndrome, researchers reported.

Findings also suggested that repeated, regular exposure to music altered the activity of certain genes in particular brain regions, yielding clues as to the biologic mechanisms through which the intervention works.

The study, “Music-Based Intervention Ameliorates mMecp2-Loss-Mediated Sociability Repression in Mice through the Prefrontal Cortex FNDC5/BDNF Pathway,” was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

Music therapy is known to be helpful for some Rett syndrome patients, with prior research suggesting that music can improve social interaction and communication skills among children with the disorder. However, the biological basis for such improvements are not clear.

A team of researchers in Taiwan conducted a series of tests to better understand the effects of music in Rett syndrome. In these tests, mice with mecp2 mutations — the most common cause of Rett syndrome — were exposed to music, white noise, or to no noise (as a control group) for six hours each day for three weeks.

Notably, the team only used male mice, as male mice develop Rett-like symptoms very quickly in this model. Since Rett syndrome in humans almost exclusively affects females, the use of male mice was noted as a study limitation.

Six compositions of different music forms were chosen. They included a classic Taiwanese melody, classical music, vocal music by Sarah Brightman, and music sung by a church choir.

The animals’ social aptitude was assessed by researchers recording how long the mice spend sniffing stranger mice —basically, more sociable mice are known to spend more time sniffing. Rett syndrome mice exposed to music spent significant longer time sniffing the other animals, whereas no such difference was observed for animals exposed to white noise or no noise.

“The result indicates that the music-based intervention improved one of the social parameters, sniffing intensity, in mecp2 [mutant] mice,” the researchers wrote.

In further tests, the scientists looked for biochemical changes in the mice’s brains associated with music intervention.

The team found that Rett syndrome mice had lower-than-normal expression of a gene called BDNF in the prefrontal cortex — a part of the brain involved in cognition — which codes for a protein of the same name. The BDNF protein is important for the survival and communication of nerve cells. Within the Rett model group, mice exposed to music showed higher BDNF expression in the prefrontal cortex compared with control mice or those exposed to white noise.

In the hippocampus, which is involved in memory, animals within the Rett model group also showed lower BDNF expression in the hippocampus if exposed to white noise, compared with music or with control animals.

Music was also associated with significant increases in BDNF protein levels in the hippocampus, as compared with mice in the other groups.

Gene activity of FNDC5, which codes for a protein important for muscle function and cognition, was also higher in the prefrontal cortex following music compared with white noise.

“The analysis of FNDC5/BDNF signaling pathways hinted at the complex nature of biological activity in brain tissue that the [musical] intervention may influence,” the researchers wrote, noting a need for further research to unravel these mechanisms.