Iron Deposits in Brain May Contribute to Dystonia in Rett Patients

Dystonia, or excessive involuntary muscle contractions, are linked in Rett syndrome with abnormal iron accumulation in certain brain regions, a study suggests.

The study, “Correlation of dystonia severity and iron accumulation in Rett syndrome,” was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The characteristic motor and gait symptoms of Rett typically emerge in children between the ages 1 and 4, before stabilizing by age 10. But for some, deterioration can continue into adolescence and adulthood, with muscle weakness and rigidity, as well as motor traits that are hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease — namely bradykinesia (slow movement) and dystonia.

Although the relationship between Rett and parkinsonian features is not fully understood, it may be related to problems with the MECP2 protein that are evident in Rett, and to a brain pathway driven by the chemical messenger dopamine that is affected in Parkinson’s. Unusual iron accumulation in dopamine-regulated brain regions has been reported in a wide range of neurodegenerative diseases, the researchers noted, prompting scientists to suspect it might lead to parkinsonianism.

Studies have found iron accumulation in dopaminergic brain regions of Parkinson’s patients. But age-related changes in iron content in Rett patients, and whether they correlate with parkinsonian features and dystonia severity, remain unclear.

Researchers in Taiwan evaluated 17 Rett patients with MECP2 mutations (age 4 to 28, all female) and 26 age-matched healthy people serving as controls.

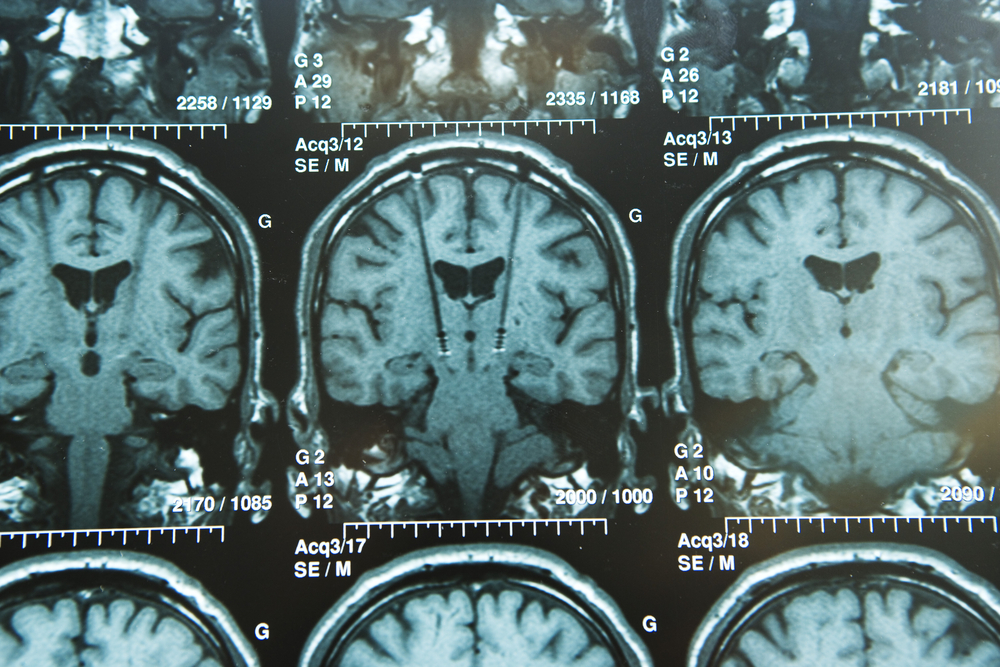

They used susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) — an MRI technique that detects compounds that distort the magnetic field — to assess iron accumulation in five dopamine-regulated brain regions: the substantia nigra (SN), globus pallidus (GP), caudate nucleus, putamen, and thalamus. Four are part of the basal ganglia, which controls voluntary movement, while the thalamus is part of its information relay system.

Ten patients, all older than age 10, had significantly more severe dystonia than did the seven younger patients in measures taken with both the Unified Dystonia Rating Scale and Fahn–Marsden Dystonia Rating Scale.

Two SWI image analysis methods, visual grading and contrast ratio, were used to evaluate brain iron deposition. Under the visual scale, both controls and Rett patients showed no to mild iron accumulation in the caudate, putamen, and thalamus. But in the GP, Rett patients relative to controls had more areas of moderate (33% vs 11%) and severe (0.6% vs. 0%) iron accumulation. Iron buildup in the SN was significantly more severe in Rett patients compared to controls.

Using contrast ratios, iron accumulation was significantly higher in the putamen and caudate of Rett patients in comparison with controls.

Age correlated moderately to highly with iron accumulation in both patients and controls, although not in all five brain regions of those with Rett. Iron accumulation in the SN, GP, and putamen was associated with dystonia severity.

“This result revealed a new perspective on how unusual iron accumulation accelerates [nervous system] damage and aging in the RTT [Rett] brain,” the researchers wrote, adding that “further longitudinal studies are mandatory for clarification of early aging and the change in iron accumulation in the brains of individuals with RTT [Rett].”

Among the study’s limitations, they said, were its small sample size and limited age range, as well as the differing results with visual grading and contrast ratio.